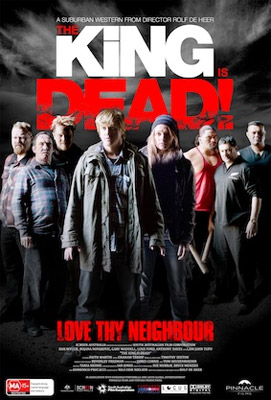

Rolf de Heer on The King is Dead

Rolf de Heer on The King is Dead

Cast: Dan Wyllie, Bojana Novakovic, Gary Waddell, Luke Ford, Anthony Hayes, Lani John Tupu

Director: Rolf de Heer

Genre: Thriller, Drama

Rated: MA

Running Time: 102 minutes

Synopsis: Open inspection at the house-for-sale in the quiet, leafy neighbourhood... Max, science teacher, and Therese, tax accountant, decide that here is the house for them.

Unsuspecting, they buy and move in, finding a nice family on one side and, well, "interesting" on the other. But interesting soon becomes loud, and loud soon becomes intolerable and when the intolerable becomes the violent, and the police are powerless to do anything, and the community lawyer suggests ear plugs, Max and Therese are forced to try and solve the problem of the neighbour from hell themselves...and end up with a corpse on their hands.

But even that's not the worst of it, because the corpse from hell has friends...and even worse, enemies...

Release Date: July 12th, 2012, exclusive to Cinema Nova

About the Production

February, 1961...I'm ten years old, recently arrived in Australia and living in outer suburban Sydney. The neighbours, whose house is two metres from ours, have no fewer than seventeen Afghan hounds living inside their house. Every Sunday morning at around 0630 (and for some unknown reason, only on Sunday mornings at around 0630), these seventeen Afghan hounds start howling in concert, howling as if the moon were on fire.

Every Sunday morning at that time, when the howling shows no sign of abating, my father yells out, very loudly from the bed in which he's still trying to sleep, and with heavy Dutch accent, "SHUT UP, YOU YELLOW STINKERS!!", followed by a string of curses in Dutch. As the months go on and he begins to master the English language, this becomes "...YOU YELLOW BASTARDS!!" and not long after, "...YOU YELLOW STINKING BASTARDS!!".

Relations with the neighbours begin to break down. Soon, even the children on both sides stop talking to each other. I don't know it yet, but the idea for "The King Is Dead!" is born.

Over the next thirty or forty years, I lived in many houses...twenty seven as best as I can recall. I lived in houses in Sydney, in Melbourne, in Adelaide. I lived in houses in the inner suburbs, the outer suburbs, the inner West, the Eastern Suburbs, the Northern Suburbs. And, for better or for worse, all of these houses had neighbours.

I remember a semi-detached house where the old man next door would refuse to acknowledge my existence, no matter what greeting I called to him. He seemed to have infected the entire neighbourhood because not once in fourteen months did I meet a single resident of the street. But most nights I would hear the old man next door, stumbling around and into things, muttering curses at no one who was there.

I remember the Irish couple, neighbours in a tightly packed row of terraces in the inner city. Through paper-thin walls, night after night, I would hear the tone of their arguments escalate as they drank. When they started screaming at each other I knew that at any moment the argument would shift from the verbal to the physical and that the first "thud" was imminent.

One night, after a few weeks of this, the female of the couple climbed over the fence into my place at two in the morning, face bruised, shaking. Her beloved appeared to have given her a thorough going over. No, she didn't want the police called, she just wanted another drink, and then another. Some nights later it was his turn...he climbed over the fence, nose bleeding, face scratched, defeated, just wanting another drink. The night someone else in the street called the police they both climbed over, helping each other across. It was tragic, it was sleep-depriving but it was also funny.

Not so funny was the neighbour who used to thrash her young daughter, who used to scream, "Mummy, Mummy, I love you!" as she was being beaten. It was a place where I could not stay long. An awareness grew in me that in our society of shifting values, neighbour problems were becoming endemic. Some close friends ended up in a celebrated, costly and vigorously contested court case over a neighbourly stoush that had spiralled out of control. The details were tawdry and my friends lost the case, yet they seemed like such reasonable people to me. How had they been drawn so far into this vortex? It seemed beyond explanation.

It was only some while later, co-incident with a steep rise in the use of amphetamines in the area in which I was then living, that I learnt for myself how this can happen. I was, at the time, living in a house in a peaceful suburban street, an area of immigrant families made good and neat front gardens that made the neighbourhood a delight to walk.

It started innocently enough, with a party in the house next door that was just that bit louder than easily tolerable and went just that bit longer than reasonable. Some days later, another party, longer, louder. Soon there was a party almost every night, usually all night. Very soon they couldn't be called parties anymore. That house next door sank into an amphetamine-fuelled hell for the neighbourhood that lasted for almost three years, and nothing could be done about it. The police professed themselves powerless to stop it. Legal advice gave less than no comfort. The only advice that could reasonably be acted upon was for people to move house. I didn't want to move house. Being a fictionalist, I began daydreaming of other solutions.

The dreams were vivid, and imaginative. Whole scenarios took place in my head that had the noisy neighbours leaving rather than myself, and their imaginary departure was caused entirely by my imaginary actions. But it was when I caught myself considering these imaginary actions perhaps a little too seriously that I knew I had to stop devising them in the real world, and begin thinking about them in the realm of fiction, maybe as a film idea that could be developed.

The dreams were vivid, and imaginative. Whole scenarios took place in my head that had the noisy neighbours leaving rather than myself, and their imaginary departure was caused entirely by my imaginary actions. But it was when I caught myself considering these imaginary actions perhaps a little too seriously that I knew I had to stop devising them in the real world, and begin thinking about them in the realm of fiction, maybe as a film idea that could be developed. Luckily, neighbours can change, and mine did. The neighbourhood became peaceful once again and life resumed much as before, except now the idea for "The King Is Dead!" had grown up somewhat, had a consciousness and some sort of possible form.

It's a year or so later, and I'm struggling with a screenplay I'm meant to hand in to one of the funding agencies. It's not working, the central idea of the screenplay is not working, and I ring up the agency and suggest I return the money they've so far forwarded to me.

The voice at the other end of the phone is sympathetic, but the bureaucracy involved in handing money back is too complicated. I'm counselled to write anything I want; it doesn't have to be the idea that was funded.

I've set aside this time to write, and I want to get this monkey of a due-script off my back, so I agree. I think about what to write and, of course, despite the fact that I now have quiet neighbours, the ideas for "The King Is Dead!" flood back, embellished as they've become by their having been locked in my unconscious for the time that they have.

I write the screenplay, enjoying the distance from reality yet the experiential knowledge that also goes into it. I'm free to manipulate anything I think, because all that matters is story and character and that it be story and character well-told. It takes on a life of its own and ends up in places that surprise even me. But I'm happy enough with it to consider making it.

I hand the script in to the agency and send it out to three or four other people, but before it can get any traction at all, I'm commissioned by an overseas producer to adapt a very fine novel set in another country. I'm also to direct it. My interests move naturally in that direction. The screenplay of "The King Is Dead!" joins several other screenplays of mine, ones that sit and wait resurrection on their chosen day.

Two years or three years later, circumstances co-incide. I'm working on a bigger project, one that will take significant time to get going, if ever. A long-held dream to go rural for my personal living situation is materialising, but there are delays in having anywhere to live on our new property. Much to the regret of our city neighbours, with whom we get on famously, we're going to be selling our house and moving, but not quite yet. Through the delays, I increasingly need to do something in the meantime. And what I do is make films.

An idea forms...why not do "The King!", very soon, at a low budget?

The idea becomes bolder...why not shoot it here, in this house we're going to sell anyway, using most everything in it as set dressing, and shoot the locations of the neighbours of the script, both good and bad, at the houses of our real neighbours on each side? What a way to shoot this film! What a way to control the budget! The house of Neighbour One, the good ones, can be as is, we barely see inside it in the script. The house of the other neighbour, the King of the script, will need a fair amount of work on the outside, and the inside will have to be a set as it doesn't remotely resemble what's there, but it'll work...all the over-the-fence stuff will be authentically in place, plus we'll be shooting the whole film in effectively one location plus one set.

The idea quickly takes hold. By clever management we find we can go even further...we can use the spare rooms of the main house location, our house, as the production office, the makeup room, the wardrobe department. If we keep the crew tight enough, everyone can somehow fit in here. It's time to do a budget, and to see how sensibly low we can keep it.

Apart from my usual collaborators, the first people I spoke to about doing the project this way were the neighbours. Without their cooperation it would still have been possible, but much more difficult and more expensive. The neighbours on one side embraced the idea enthusiastically and were willing to go to any lengths to help. The neighbour on the other side went with it, but more cautiously...after all, we had to build a false front onto his house, and he was being asked to grow his grass into a long and tangled mess. But as time went on, he too became an enthusiastic supporter of the project.

Through necessity and invention, we worked out how to keep the budget low. As a consequence, quite quickly there was sufficient interest in the project for us to be confident that the film would be financed in short order.

And so it proved to be. A patchwork of finance was put together. Principal investor was Screen Australia, with 40% of the budget. The South Australian Film Corporation committed early, and also agreed to cashflow the Producer Offset. Pinnacle Films took Australian rights for an advance, Fandango Portobello international sales rights also for an advance and Locus Global Entertainment from China came in towards the end with an investment, later converted to the purchase of Chinese rights.

And so it proved to be. A patchwork of finance was put together. Principal investor was Screen Australia, with 40% of the budget. The South Australian Film Corporation committed early, and also agreed to cashflow the Producer Offset. Pinnacle Films took Australian rights for an advance, Fandango Portobello international sales rights also for an advance and Locus Global Entertainment from China came in towards the end with an investment, later converted to the purchase of Chinese rights. With apologies to the very difficult and very necessary profession of focus pullers on films, one of my theories of film making goes something like this: if you get the script right and you cast it well, you can practically shoot it out of focus and it'll still work.

I don't mean one can be careless about focus (I could equally say, without focus there is no film), but I mean that casting a film well is the next most important thing in the entire process after getting the script right, which is the most important thing. To this end, considering the sort of film "The King Is Dead!" was going to be, I went through a more extensive and rigorous casting process than I have on practically any film I've done.

There were eleven roles of substance (meaning performers who would be with us for more than just a day or two), as well as numbers of bit parts. As the entire film was being shot in South Australia, and as the acting pool there, though talented, is quite limited, we had some allowance in the budget to bring in actors from interstate, and we had the necessary luxury of a casting agent, Faith Martin, in Sydney.

I also co-opted an Adelaide actor/friend, Paul Blackwell, to help with the Adelaide casting.

I don't like to screentest...some good actors are bad at screentesting and some actors who screentest well turn out to be pretty average actors. And headshots mean nothing to me. I prefer in the first place to see material on screen, which might determine whether an actor is interesting in the role for me. I then like to meet them, speak with them normally (inasmuch as that is possible when an actor knows they're up for a role)...a casual conversation in a pub is often more useful than a discussion in a meeting room, which inevitably ends up something of a formal interview.

Everything combined then hopefully tells me whether the essence I'm seeking in the character can be found in that particular actor, whether between the actor and I we can come up with what is for me necessary for the script.

But it doesn't end there. Even if that essence is there, the dynamic between all the actors playing all the characters has to be right, and on this project, what was particularly complex were the threat dynamics.

There had only been one actor who had occurred to me for a role while I was writing the script, and that was Gary Waddell as King. I'd seen Gary Waddell's kinetic performance in that Australian classic, Pure Shit, and I'd met him and had cause to spend an evening in his company some years ago. As the idea for the film was developing into a script, Gary Waddell's essence began inhabiting the character I was writing. Faith instantly agreed that Gary Waddell would make a great King and so she arranged for him to come in for a chat.

Speaking to an actor you know you're going to offer the role to is almost as difficult as interviewing an actor who you know you're definitely not going to offer a role to, but awkward though that interview was, nothing about it changed my mind that Gary Waddell would make a great King. But now I needed to cast everyone else around him.

The characters of Max and Therese, the leads and occupants of the central house, had to be on roughly the same threat level as King...in a day-to-day sense they should not feel threatened by him, nor should they be capable of making King feel physically threatened.

But Max and Therese should definitely be able to feel threatened by Shrek, and to a lesser degree, by Escobar. And then complicating that, just as we think Shrek is the ultimate physical threat, along come the Maoris and we find out that here's a different level of threat altogether.

And combined with all those requirements, Max and Therese should also work absolutely convincingly as a couple. Too many films let themselves down by failing to convince in this area...some otherwise perfectly good films don't quite work because the couple dynamics don't quite convince.

And so casting became a long and almost tortuous process, one that must have driven some people close to exasperation. I wouldn't commit to anyone until I could commit to the entire set, and that kept shifting as new actors came into consideration and suddenly the set of actors that was developing no longer worked at all.

Actors would be available one minute, and not the next. Or a particularly interesting actor was probably going to be available, but we won't know for a couple of days, which would turn into a week. My shortlists grew into longlists, then were pared back down to shortlists again. Then someone who'd been pared off would make another appearance. And all the while Faith Martin would come up with new suggestions, and more material for me to look at.

The longer it all took, the more difficult it became for the costume department, because the window between casting almost all the main roles and shooting became shorter and shorter. I lucked out one afternoon in Sydney with the three Maoris, who I didn't think I had any chance of improving upon no matter what happened with the rest of the casting. Casting them took the pressure off for a few days as the costume department finally had something more than bit parts to dress.

Meanwhile, through all this, the rest of the pre-production sailed on smoothly. More and more people took up office in the house that was also the set that was also where I lived, and somehow they all fitted. Much of the art department's work had been done before they started, and they could concentrate on the false exterior and dressing of King's place and the set of the interior of King's place in the studio, just a few kilometres up the road.

On the other side of the central house, neighbour Sam, a chef in past life (nothing like the character in the film) but now primary carer for his and Anna's three kids, had agreed to take on the catering for the film. He cleared out his carport and the adjoining area at the side of his house away from the main set and converted it into not only the place where cast and crew could sit down under cover for breakfast, lunch or dinner, but also a place where cast could spend time off set and crew could get their off-set work done.

Then, barely a week before start of shoot, the missing bulk of the casting fell into place...Dan Wyllie, who'd been a suggestion of Faith Martin's very early on, and who had been on and off lists since that time, suddenly clicked for me as Max with a particular combination of actors playing the other roles. The nature of how he engages with audience, with warmth and humour, convinced me I'd want to spend an hour and three-quarters in a darkened cinema with him.

Therese would therefore be played by Bojana Novakovic, whom I'd first spoken to by Skype in Los Angeles and whom I'd seen in Melbourne the first time I went there to cast. She'd been a front-runner a number of times, and completely off the list at other times, depending on the likely Max. But paired with Dan Wyllie there was no question but that she'd be right.

The role of Shrek had been another concern. Luke Ford had been put up for the role of Max, but with him as Max, we'd have had nowhere to go in terms of threat dynamic with Shrek, which was what gave me the glimmerings of the idea to cast Luke Ford as Shrek in the first place. But from the films Luke Ford has done, and even from meeting him, he was such a "nice" guy, so apparently straight, that it was hard to imagine him as a Shrek, despite his physicality.

But I reminded myself, never underestimate a good actor. When we came closer to having to lock the roles off and I still hadn't found a Shrek, I spoke to Luke Ford about what might be done with Shrek and where we might go with him. And Luke Ford convinced me by that conversation that he had the capacity to go there, even though it was a long way from where he'd been as an actor. And go there he did.

The only difficulty with the role of Escobar was that the choice was too great. I'd seen maybe eight actors who could have played the role beautifully. There were four left on my short list, each of whom would have made a very different, but terrific, Escobar. Hard though it was to choose, it was also easy to choose Anthony Hayes, who is not only an actor, but also a film director. And I like having other film directors working on a film that I'm doing, no matter what their capacity.

The "good" neighbours, Otto, Maria and little Mirabelle, had all been cast from Adelaide and with this came a remarkable story. During our early casting sessions in Sydney, Faith Martin had asked me if I knew of the Adelaide actress Michaela Cantwell, and what had happened to her. I did...Michaela Cantwell, in her thirties, had suffered a major stroke some time before, and was undergoing a painful, long journey of rehabilitation. Faith Martin talked of going to see her soon.

Thoughts mulled, then suddenly clicked. I suggested to Faith Martin that we cast Michaela Cantwell. Although Faith Martin liked the idea, she was uncertain how Michaela Cantwell was...was she in a wheelchair, or on crutches, what were her problems? I said I didn't think it mattered...the nature of the role was such that we could adapt to any eventuality. Is she on crutches?

Then so shall the character be on crutches...one doesn't always have to explain these things, it would just be part of that character. And it ought to help Michaela Cantwell's rehabilitation. So we did cast Michaela Cantwell, sight unseen. Some time later I cast Roman Vaculik, also in the end from Adelaide, as Michaela Cantwell's screen husband, Otto. Roman Vaculik knew Michaela Cantwell, and was terrific in helping her through the process...she was very comfortable with him. Later I found out that Roman Vaculik had been there the night Michaela Cantwell had had her stroke. They were celebrating the end of a run of a play they were in together when it happened, and afterwards Roman Vaculik was one of only three people she remembered from the months leading up to her stroke. Roman Vaculik's casting had been a divine stroke of luck.

Then so shall the character be on crutches...one doesn't always have to explain these things, it would just be part of that character. And it ought to help Michaela Cantwell's rehabilitation. So we did cast Michaela Cantwell, sight unseen. Some time later I cast Roman Vaculik, also in the end from Adelaide, as Michaela Cantwell's screen husband, Otto. Roman Vaculik knew Michaela Cantwell, and was terrific in helping her through the process...she was very comfortable with him. Later I found out that Roman Vaculik had been there the night Michaela Cantwell had had her stroke. They were celebrating the end of a run of a play they were in together when it happened, and afterwards Roman Vaculik was one of only three people she remembered from the months leading up to her stroke. Roman Vaculik's casting had been a divine stroke of luck. Deep in pre-production and I finally get around to something I've been putting off...we need a rap song. Graham (Tardif, composer) and I had decided we'd do one of our own, so that it would be (a) affordable and (b) as close as possible to exactly the right tone for the film. Graham Tardif and I had previously done the ten songs for The Tracker together (he'd provide the music and I'd then write the words) and we'd decided on a similar process with the rap song. And Graham Tardif's composition of the rap bed has arrived.

But I know little about rap, and almost nothing about gangsta rap, so I go to the CD store that has just about everything and find out fairly quickly (thank heavens for friendly and informed sales assistants). I come home with a couple of CDs of gangsta rap and listen to them.

Gangsta rap very quickly becomes not my favourite form of music. It's violent and misogynistic and crude and altogether generally pretty unpleasant. But I listen to the two CDs again...and again. There's skill there, and without the words there's occasionally some good "music", but I'm finding it hard to think that I can come up words appropriate to the genre.

I immerse myself in thoughts of the world behind those two CDs. I immerse myself in the character of Shrek, who is the character who is attached to this song, so much so that he tries to learn the words to it. The headphones are on my head for hour after hour, and gradually the ideas, then the specific words that give life to those ideas, start to form. I find I have to almost be able to rap myself in order to write this song.

Finally the words are there in such a way that it suits me. I walk down the hallway to the production office...I need to try them out with an audience. I perform "Ah'm Tha One!" for Julie B and Fiona L...a look of horror grows on their faces and then suddenly they both burst out laughing, and continue to laugh as I try and keep the rap going. I'm initially dismayed, then realise that the sight/sound of me performing gangsta rap is so unusual, so bizarre, that laughter is the only reaction possible.

I resolve to limit my performance of the piece to necessity. By circuitous connection, we find that the person we can find who is best suited to being the actual performer of this rap is an actor who was on the shortlist to play Escobar, Justin Rosniak. Justin Rosniak flies in the weekend before shoot to record and we have our rap song. It becomes wildly popular on set and there's even a suggestion I do this sort of thing as a sideline, but my tastes run elsewhere.

With cast (and song) finally in place, the final few days of preproduction hurtle past at breakneck speed. Then begins a shoot a little unlike any I've experienced...studied, quiet, carefully correct, a minimum of fuss, actors concentrated, everyone giving of themselves and communicating well...far less chaos than a normal shoot would bring.

The schedule has us shoot many things in script sequence, a great help to actors who have not had a chance to rehearse together (they've assembled from too many different parts of the world, and they're doing a film with a budget such as to discount any such possibility). The characters begin to form and quite soon the emotional heart of the film begins to show itself, the relationship between Max and Therese. Dan Wyllie and Bojana Novakovic are both deeply thoughtful about their roles, and quickly find those unscripted little affectionate touches that make them so convincingly a couple.

In visual and emotional contrast, we all enjoy it every time we do something with Gary Waddell, Luke Ford and Anthony Hayes. King, Shrek and Escobar, the rogues next door, are colourful and mighty entertaining, and a pleasure to work with.

We have a strange week for the last at the location...the entire main house is wrapped in black plastic as we shoot the night scenes in the bedroom and living room. For the week I see virtually no daylight, as this is also the house I still sleep in and have therefore no need to leave. Then, bizarrely, we have two weeks in the studio, which is lit entirely for night, and where I arrive in the mornings before daylight and leave after dark. For three weeks I seem to exist in a sort of twilight zone of perpetual night.

But the studio shoot is a real pleasure. We start with just Dan Wyllie and Bojana Novakovic, as Max breaks into King's and is then joined by Therese. Then King turns up. Gary Waddell, playing King, amazes...for almost two weeks he has to be dead, and for a fair proportion of that, dead in an upright position, half-hanging by a rope. His focus is unrelenting.

Then Shrek and Escobar enter the mix, and the action heats up and becomes confined to one small part of the set, a sort of anteroom/hallway. By the time the three Maoris join in, there are eight actors and a film crew in a tiny space...for a week. Impossible to try and do if not in a set, where walls can be removed and replaced.

The Maoris add a real spirit to the end of the shoot. Lani Tupu, Boss Maori, is a very experienced actor, both stage and film, but for Jack Wetere (Man Mountain) and Richard Bennett (Silent Maori) these speaking roles are a real opportunity, and they're determined to show the people at home that they're actors, not just hulking extras. For Jack, playing Man Mountain has its problems. Man Mountain is a steroid-fuelled, body building, baseball bat-wielding gangster with a touch of Tourette's syndrome...the frequency and intensity of his swearing ranks up there with the best of them. But Jack himself, although of splendidly suitable physique, is a Mormon, a gentle man with a ready smile who never swears. He worries a little about what his mother will think, but he throws himself into the part with gusto.

Richard Bennett, as Silent Maori (also a baseball bat-wielding gangster), fits the role well...although he's over 200 cms tall (6'7"), he speaks very quietly when he does have something to say, but he too has his issues...the pressure on him of his sudden burst of dialogue towards the end has him mix and mangle all the words...nothing will come out in the correct sequence or meaning, no matter how well he's learnt it or how hard he tries. After an hour or so of trying, we clear the set of everyone other than Jonesy holding the camera and me standing next to camera as Richard Bennett's eye-line. We practise and rehearse on camera, going over and over the words. Slowly the pressure reduces and eventually the words start to come out right, until finally Richard manages a few takes that I'm satisfied with. He is most relieved, and very proud to have finally achieved his speaking part.

But I thank my lucky stars that of the three Maoris it is Lani, who has such ease with acting, who has almost all the dialogue. Then it was onto the last day, the atmosphere lightening by the hour as we get closer to the end. It's as if we're breaking up for the Christmas holidays, although it's completely the wrong time of year for that. But for most of the crew and the cast, it is the end of the project, one that was among their more pleasant shooting experiences.

But I thank my lucky stars that of the three Maoris it is Lani, who has such ease with acting, who has almost all the dialogue. Then it was onto the last day, the atmosphere lightening by the hour as we get closer to the end. It's as if we're breaking up for the Christmas holidays, although it's completely the wrong time of year for that. But for most of the crew and the cast, it is the end of the project, one that was among their more pleasant shooting experiences.The King Is Dead! is film about neighbours, good neighbours as well as the neighbours from hell. During its making, almost everyone who came into contact with the project had a story to tell about neighbours, usually tending towards the neighbours from hell. The theme seems a universal one.

It was a double irony then, that the film was made in large part possible through neighbourly co-operation, and that I found myself moving, during post production, to a place where my nearest neighbours are almost two kilometres away. I've gained peace and solitude and communion with the animals and birds, but I've lost something too, and that is the communion with good neighbours, and how interesting bad neighbours can be, what they can bring to the imagination. I suspect that The King! is my first but also my last film that has much anything to do with neighbours.

MORE